Government Job STAR Response Builder

Government jobs require specific examples of your experience. Use this tool to structure your responses using the STAR method: Situation, Task, Action, Result.

Your Government-Ready Response

Example will appear here

Getting hired by the government isn’t like applying for a job at a startup or a retail chain. There’s no quick LinkedIn message, no coffee chat with a hiring manager, and no ‘just send your CV’ approach. The process is structured, slow, and often confusing. But it’s not impossible. And it’s not as hard as people make it sound-if you know what to do.

It’s not about who you know, it’s about what you prove

One of the biggest myths about government jobs is that you need connections. That’s not true. In most countries, including the UK, the US, Canada, and Australia, hiring is governed by strict rules to prevent favouritism. Your application is scored based on what’s on paper, not who you had dinner with. The system is designed to be fair. But that also means you can’t wing it.

Every government job posting lists specific competencies. For example, if you’re applying for a policy analyst role in the Department for Work and Pensions, they’ll want evidence of your ability to analyse data, write clear reports, and work within legal frameworks. Not just ‘good communication skills’-they want examples. Real ones. Like: ‘Led a team to reduce benefit fraud claims by 18% using cross-departmental data matching.’ That’s the kind of detail that moves you from the pile to the shortlist.

The application form is the real test

Most government jobs don’t ask for a CV. They ask for a detailed application form. These forms are long. Sometimes 10-15 pages. And they’re not optional. If you skip a section, your application gets rejected automatically. No exceptions.

Each question is scored against a marking scheme. For example, one question might say: ‘Describe a time you managed a project under tight deadlines.’ The assessors are looking for:

- Context: What was the project?

- Action: What did YOU do?

- Result: What was the outcome? With numbers if possible.

Write like you’re explaining it to someone who has no idea what you do. No jargon. No fluff. Just facts. And don’t reuse the same example for every question. If you use your university group project for one answer, find a different example for the next-maybe from your volunteer work or previous job.

Exams are real-and they’re not easy

Many government roles require a written test. In the UK, civil service roles often have a situational judgement test (SJT) and a numerical reasoning test. In the US, federal jobs may require a clerical or typing test. In Canada, public service exams often include written communication assessments.

These aren’t trick questions. But they’re designed to filter out people who haven’t prepared. The SJT, for example, gives you workplace scenarios and asks you to rank responses by effectiveness. If you pick the ‘nice’ answer instead of the ‘correct’ one (based on public service values like integrity, accountability, and impartiality), you’ll score low.

Practice tests are free. The UK’s Civil Service Fast Stream site has sample SJTs. The US Office of Personnel Management offers practice exams. Don’t just skim them-time yourself. Do them under pressure. Treat them like a real exam.

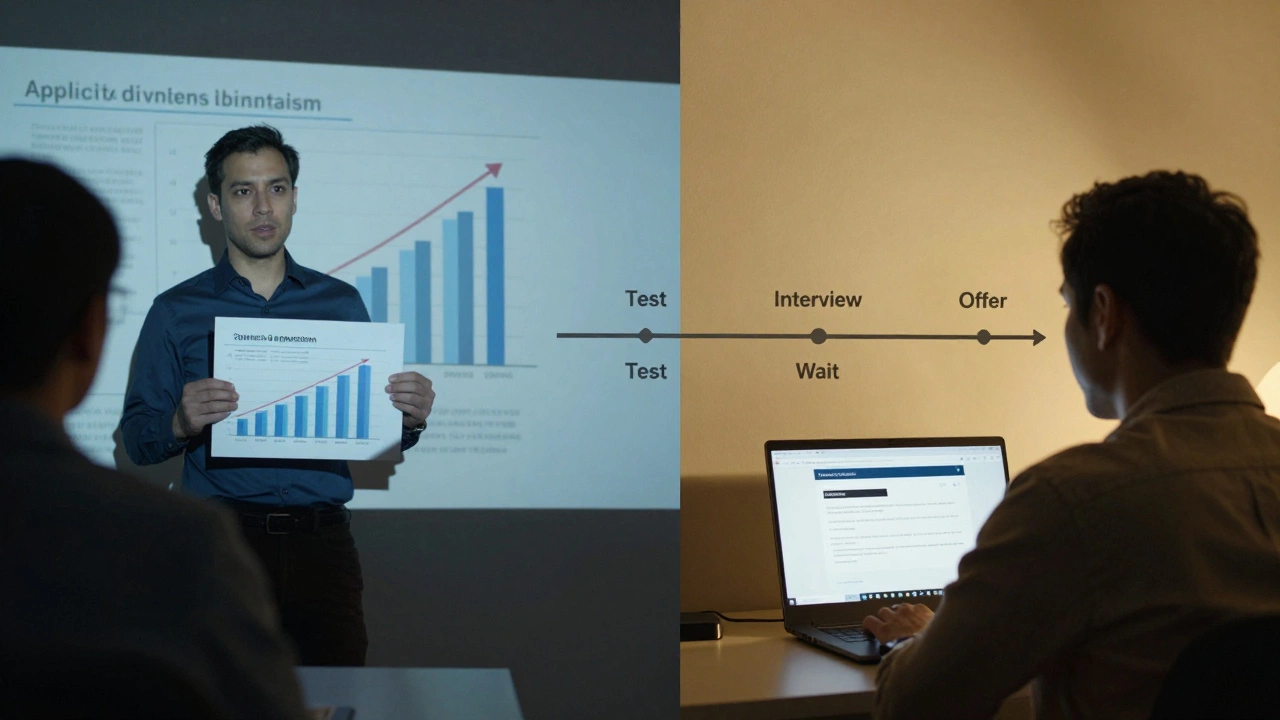

Interviews are structured, not casual

Government interviews are rarely the ‘tell me about yourself’ kind. They’re competency-based. You’ll be asked to give examples using the STAR method: Situation, Task, Action, Result. And you’ll be scored on each part.

One common mistake? People give vague answers. ‘I improved team morale’ isn’t enough. ‘I noticed staff were missing deadlines because of unclear priorities, so I introduced a weekly planning board and tracked progress in team meetings. Absenteeism dropped by 22% over three months.’ That’s the difference.

Also, be ready for questions about ethics. ‘What would you do if you saw a colleague misusing public funds?’ There’s no right personality answer here-only the right policy answer. Know the core values of the department you’re applying to. If it’s the NHS, they care about patient safety. If it’s the tax office, they care about compliance and fairness.

The waiting game is real

From application to offer, it can take 3 to 6 months. Sometimes longer. There’s no way around it. You’ll apply, hear nothing for weeks, then get an email saying you’ve been shortlisted. Then another wait. Then an interview. Then another wait. Then a reference check. Then an offer.

Don’t let this discourage you. Use the time wisely. If you’re waiting after an interview, send a short thank-you email. Not to beg, but to reinforce your fit. ‘Thank you for the opportunity. I’ve been reflecting on our discussion about digital transformation in public services, and I’ve been reading the latest White Paper on modernising service delivery-especially the section on user-centred design.’ That kind of thing shows you’re serious.

What most people get wrong

Most applicants treat government jobs like any other job. They copy-paste their CV. They write generic cover letters. They skip the practice tests. They think ‘I have a degree, I’ll get in.’ That’s not how it works.

Government hiring is a system. And like any system, it rewards preparation over talent alone. You don’t need to be the smartest person in the room. You need to be the most prepared.

People who succeed:

- Read the job description like a legal document

- Use the exact keywords from the competency framework

- Practice tests until they can do them blindfolded

- Know the department’s recent reports and priorities

- Apply to multiple roles-even if they’re not perfect matches

One person I know applied to seven different government roles over 18 months. Got rejected four times. Got interviewed three times. Finally got a role as a senior analyst in the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. She didn’t have a fancy degree. She had a track record of following the rules-and doing the work.

It’s not impossible. It’s just different.

Getting hired by the government isn’t about luck. It’s not about connections. It’s about understanding the system and playing it right. The barrier isn’t your background, your age, or your experience. It’s your approach.

If you treat it like a project-break it down, prep thoroughly, track your progress-you’ll get there. Most people give up before they even get to the interview. Don’t be one of them.